History revisited in Kolkata as the English translation of an award-winning Urdu work on Nawab Wajid Ali Shah is launched at ICCR, celebrating Awadh’s cultural legacy.

Kolkata | 15 February 2026

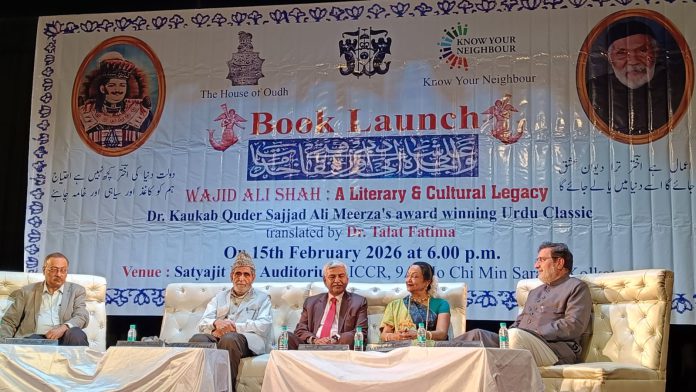

History has a way of returning when it refuses to be forgotten. On Sunday evening at the Satyajit Ray Auditorium, that return took the form of a book launch that was as much about scholarship as it was about cultural memory. The House of Oudh, in collaboration with Know Your Neighbour, presented the English translation of a celebrated Urdu work on Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, originally authored by Dr. Kaukab Quder Sajjad Ali Meerza and now translated by his daughter, Dr. Talat Fatima.

The gathering drew scholars, artists, students, and admirers of Awadh’s last ruler—many of whom have long believed that History had not been entirely fair to the poet-king. The original volume, honoured with a Classic Award, examines the cultural, literary, and artistic dimensions of Wajid Ali Shah’s reign, challenging simplistic narratives that have persisted for generations.

The programme opened with an announcement by Smt. Vaijayanti Bose, followed by an inaugural song by the Sarkar Group. Janab Irfan Ali Mirza delivered the welcome address before the felicitation ceremony began. The Chief Guest, Prof. Zaman Azurdah, along with Special Guests Dr. Sudipta Mitra, Mr. Sunil Misraji, Smt. Rupa Chakraborty, and family representative Shakeel Hasan Shamsi, were escorted to the dais and honoured with shawls, bouquets, mementoes, and the Tricolour.

In his address, Prof. Azurdah spoke passionately about the composite Ganga-Jamuni culture that flourished in Awadh. He reflected on how Wajid Ali Shah’s court nurtured poetry, music, and refinement, creating a civilisational ethos that transcended religious and linguistic divides. He lamented the historic injustices meted out to the ruler and argued that the damage inflicted upon Lucknow’s cultural ecosystem continues to echo in the marginalisation of Urdu. Quoting a poignant couplet, he reminded the gathering that historical wrongs often outlive the moments that caused them.

Dr. Talat Fatima, in her remarks, described the translation as a demanding intellectual journey. The original work, rich in Persian, Urdu, Hindi and Braj expressions, required extensive consultation and careful rendering. She emphasised that much of the world’s scholarship circulates in English and observed that translating the text would allow it to travel beyond linguistic confines.

While acknowledging the sincerity of her intent and applauding the diligence evident in the translation, one cannot entirely agree with the assertion that English alone serves as the gateway to global readership. Languages carry their own universes; Urdu itself has crossed oceans and generations without surrendering its grace. To suggest that international relevance depends solely on English risks underestimating the intrinsic power of other tongues. That said, Dr. Fatima’s effort deserves genuine praise. Translating such a layered text is no small feat, and she has rendered a valuable service in making her father’s research accessible to new readers. At moments, however, her remarks conveyed a certain deference toward English that seemed unnecessary, particularly given the strength and dignity of the source language she was working from.

The formal release of the book was conducted on stage by family members amid applause and photography. Shakeel Hasan Shamsi recited verses from his self-composed Urdu poem, lending a personal and emotional note to the proceedings.

The inaugural session concluded before the cultural segment began. Dr. Antara Mukherjee of the West Bengal Educational Service carried the programme forward with greetings from Know Your Neighbour, highlighting the organisation’s historical engagement with the legacy of Wajid Ali Shah.

The evening then unfolded into a rich cultural tribute. Dr. Senjuti Gupta presented a ghazal recital that evoked the melancholy and elegance associated with the Awadhi court. A moderated book conversation followed, offering critical reflections on the text. The programme concluded with a Kathak performance by Shruti Ghosh, whose expressive footwork and abhinaya seemed to echo the artistic traditions once patronised in Lucknow’s royal court. Dr. Nuzhat Zahra delivered the vote of thanks, and the gathering rose for the National Anthem.

More than a book launch, the evening felt like an act of reclamation. Nearly 170 years after the exile of Wajid Ali Shah and the upheaval that altered the cultural landscape of Awadh, his descendants and admirers assembled not in lament, but in affirmation. The newly translated volume stands as both scholarship and statement—challenging inherited narratives and reopening conversations about a ruler whose artistic legacy continues to outshine the controversies imposed upon his name.