A detailed report on how Impunity shapes the withdrawal of the Dadri Akhlaq lynching case, raising grave concerns about justice, state power, and whose blood counts in India.

By Dr. Mohammad Farooque, Qalam Times News Network

Kolkata | 25 November 2025

Impunity: A Shadow Over Justice

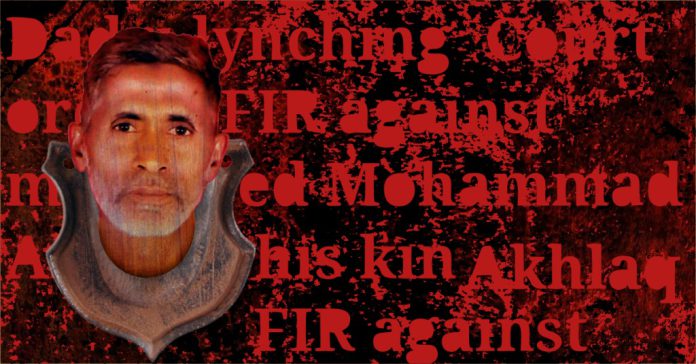

Impunity isn’t just a word here — it’s the unsettling thread running across the entire story. Ten years after Mohammad Akhlaq was lynched in Dadri’s Bisahda village, the state’s decision to withdraw all charges against the accused doesn’t merely reopen old wounds; it raises a sharper question: whose blood is cheap in this country, and for whom does the law turn into a passive spectator?

A Case That Defined a Decade

The impunity at play becomes even more evident when you revisit the night of 28 September 2015. Akhlaq, 52, and his son Danish were dragged out of their home after a temple loudspeaker announced that they had stored beef in their refrigerator. A mob beat Akhlaq to death on the spot. Danish barely survived.

The FIR named ten accused and several unidentified men, invoking serious sections of the IPC — 302, 307, 323, 504, and 506. But as the years passed, the state’s voice softened, the media’s courage faded, and public memory eroded.

The Twist in 2025

In October 2025, the Uttar Pradesh government began formal proceedings to withdraw the case entirely. The Additional District Government Counsel submitted an application under Section 321 of the CrPC, backed by the Governor’s written approval. A state laboratory’s report — which classified the recovered meat as beef — was cited as a key justification.

This case had once ignited national debate around beef consumption, cow vigilante violence, and the rise of communal tensions. Civil rights groups called Akhlaq’s killing an attack on India’s democratic fabric and launched the “Not In My Name” movement. Yet, despite public outcry, similar mob attacks persisted, disproportionately targeting Muslims under the banner of cow protection.

A System That Looks Away

Between 2015 and 2025, the case remained in limbo. Now, its quiet withdrawal raises troubling questions about political interference, witness intimidation, and the shrinking space for justice. Akhlaq’s family repeatedly spoke of fear and pressure; Danish pointed out that new names were added later while the family faced sustained threats.

Official data has only deepened the unease. In 2017, the National Crime Records Bureau attempted to create a separate category for lynching and hate crimes. The government dismissed it, calling the data “unreliable,” and later declared in Parliament that no separate statistics on lynching were maintained. If a crime has no official name, the state can pretend it never happened.

What This Withdrawal Really Signals

When a case that once stirred the conscience of an entire nation is closed without accountability, the message is bleak but unambiguous: mob violence becomes socially acceptable — as long as the victim belongs to the “wrong community.”

This is not merely a legal development; it’s a political and moral verdict.